African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) Agreement: The Next Big Thing?

June 17, 2022

INSIGHTS & OPINIONS

INSIGHTS & OPINIONS

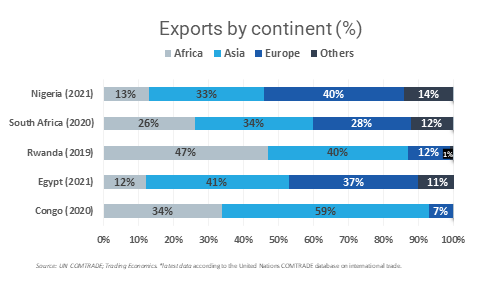

As some studies note, African economies are some of the least competitive globally. The continent is held back by 55 fragmented markets which constrain economic growth. Although these markets are among the fastest-growing economies globally, trade within the continent is one of the lowest in the world. Most of the trade is directed primarily outside the continent because African economies and infrastructure are structured to support the export of commodities to countries outside the continent. Consequently, this trade pattern has made the continent more reliant on developed economies for trade. Europe and Asia have remained the main trade partners of Africa over the years because of the continent’s high dependence on trade in primary goods, high product and market concentration of exports, and weak regional production networks. For instance, Europe and Asia are top destinations for more than 60 percent of Nigeria and South Africa’s exports in recent years. On the other hand, Rwanda, one of the fastest-growing economies globally, exports more to other African countries. One of those countries is its neighbor —Congo. Its exports to Congo in 2019 were valued at $372.59 million (32% of exports) making the country the main destination for Rwanda’s exports. Some of these exports are mineral fuels, oils, distillation products, animal products, milling products, and cereals.

In economic terms, African countries have a combined gross domestic product (GDP) of $3.4 trillion with 1.3 billion potential customers, making the continent the eighth largest economy globally. This collective size makes it much more attractive to investments both within and outside the continent to spur economic growth and create job opportunities. Conversely, many individual economies on the continent are too small to effectively compete with high-income countries in terms of trade.

Therefore, establishing a continental free trade agreement and legal framework is a step forward in unifying all the fragmented markets and customs borders to facilitate the free movement of goods, labour, and investments. And with an intra-continental trade agreement in place, industrial exports will diversify, encouraging a move away from extractive commodities such as oil and minerals. Export diversification plays an important role in improving trade within the continent as countries with more diversified exports tend to have greater shares of intra-African exports than countries with less diversified exports.

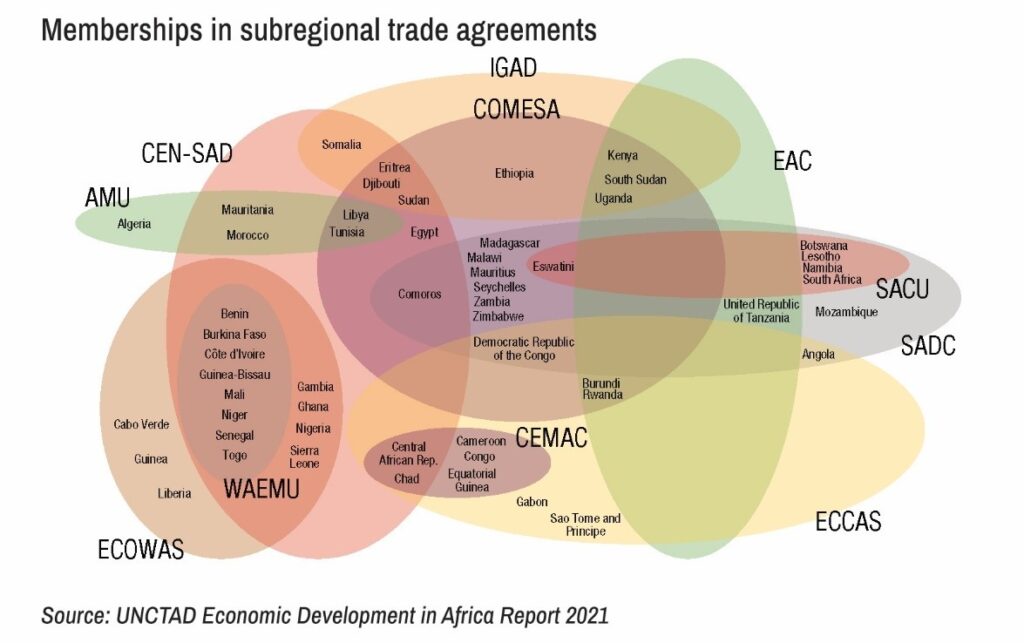

The African Union recognizes eight regional trading blocs. The goal is to realize increased regional integration through integration pillars such as customs and monetary unions, common markets, free trade areas, and common regulatory and legal frameworks. The main regional economic communities (RECs) are the Economic Organization of West African States (ECOWAS), Arab Maghreb Union (AMU), Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), East African Community (EAC), Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), Southern African Development Community (SADC), and Community of Sahel-Saharan States – CEN-SAD.

ECOWAS comprises fifteen member countries in West Africa, while ECCAS consists of eleven East and Central African countries with an aim to establish a Central African common market. EAC, one of the fastest-growing regional economic blocs in the world, brings together seven East and central African states, while SADC is composed of sixteen member states in the Southern African region. COMESA has 21 member states across Eastern and Southern regions of Africa while IGAD is an eight-country trade bloc comprising countries from the Horn of Africa, Nile valley, and African Great Lakes. Lastly, AMU comprises five Maghreb economies (Tunisia, Morocco, Mauritania, Libya, and Algeria), while the CEN-SAD consists of twenty-five member states, making it the largest regional trade bloc in Africa.

Importantly, memberships are not exclusive, and countries can belong to more than one regional trading bloc. For instance, almost half the members of COMESA belong to SADC, and nearly two-thirds of the SADC countries belong to COMESA. The economies in both trade blocs are Comoros, Malawi, Mauritius, Seychelles, Democratic Republic of Congo, Madagascar, Eswatini, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. All but two ECOWAS member states and all except one UMA member state belong to the CEN-SAD; three countries are both in EAC and ECCAS, and eight countries are both in ECCAS and CEN-SAD.

Furthermore, some regional blocs have adopted strategic frameworks and established institutions that are key to achieving further regional integration and free trade among their members. Some of these institutions include the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU), established to build a harmonized and integrated economic area in West Africa. It comprises eight ECOWAS member states, including Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte D'Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal, and Togo. The Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC) was established by six ECCAS member states that share the CFA Franc currency. The CEMAC countries are Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon. CEMAC’s primary objective is to provide a regulatory structure, maintain a common external tariff on imports and promote trade among member states in the central African region. The Southern Africa Customs Union (SACU) comprises five of sixteen SADC member states. SACU's member states include Botswana, Lesotho, South Africa, Eswatini, and Namibia. They formed a single customs territory where tariffs and other barriers are eliminated on trade between member states. Lastly, COMESA also launched the Simplified Trade Regime (STR) to simplify and streamline documentation and procedures for the clearance of small cross-border traders’ consignments, while enabling them to benefit from the common market’s preferential tariffs trading environment.

Even with all these regional trade agreements and robust institutional frameworks in place, intra-regional trade remains low. In all RECs, intra-REC exports and imports are less than 20 percent of total exports and imports, except for the Southern African Development Community (20.2 percent of total exports). Also, a high number of informal cross-border trades take place in the continent. It is reported that about 30-40 percent of intra-SADC and 40 percent of intra-COMESA trades are informal.

Figure 2. Membership in subregional trade agreements

Some active bilateral and multilateral trade agreements are the Arab Mediterranean Free Trade Agreement or Agadir Agreement, EAC-COMESA-SADC Tripartite, Malawi-South Africa Bilateral Agreement and Rwanda-DR Congo Bilateral Agreement.

Meanwhile, the Agreement only covers trade in goods and does not cover trade in services between both countries.

Although Africa has made substantial progress in improving regional integration through regional economic communities, countries still face trade issues and barriers such as harassment on borders, and lengthy and costly customs clearance procedures that make trade on the continent unattractive. These hurdles are particularly difficult to overcome, especially for retail traders. For instance, it takes Shoprite (Africa's top grocery chain) up to 1,600 documents to send one truck across regional borders.

Also, barriers to the movement of people across countries are bottlenecks that hinder intra-African trade. Business travel between African countries is a challenge for most Africans who are typically subject to expensive air tickets, onerous visa applications, and hostile customs control and border clearance. These challenges make it very difficult to conduct business operations, develop and retain skills, and distribute talents across the continent.

In an effort to improve the situation of trade on the continent, the African Union introduced a free trade agreement called the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) Agreement. One of the most ambitious trade deals in history, the agreement was signed on 21 March 2018 and entered into force on 30 May 2019. It aims to create a single continental market which would unite the continent and complement existing regional economic communities and trade agreements in Africa. AFCFTA brings together 1.3 billion people in a $3.4 trillion economic bloc representing the largest free trade area since the establishment of the World Trade Organization.

The African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement covers trade in goods and services, investment, intellectual property rights, and competition policy. It adopts mechanisms for the settlement of disputes between state parties. The trade deal addresses trade facilitation, customs cooperation, regulatory measures on sanitary standards and technical barriers on the continent. It also sets up mechanisms to address concerns regarding dumping and flooding of the African market with substandard products.

Importantly, the trade agreement provides a unique opportunity for African countries to boost productivity and create more job opportunities, further allowing them to compete in the global economy, reduce poverty, and promote inclusion. The World Bank estimates that implementing the AfCFTA would contribute to lifting an additional 30 million people from extreme poverty and 68 million people from moderate poverty by 2030. Moreover, real income gains from full implementation of the AfCFTA agreement could increase by 7 percent, or nearly US$450 billion.

The overall goal of AFCFTA is to remove tariffs on at least 90 percent of products and services to facilitate free trade on the continent, with a condition to start implementation when at least 22 countries have ratified the AFCFTA agreement. To date, 54 African Union member states have signed on to the Agreement, and 41 countries have deposited instruments of ratification of the Agreement.

The operational phase of AFCFTA officially began on 1 January 2021 in line with a declaration adopted during the 13th Extraordinary summit of the AU held in December 2020. However, no trade has taken place since then.

The AFCFTA agreement aims to:

For purposes of fulfilling and realizing the general objectives, the AFCFTA agreement states that “state parties shall progressively eliminate tariffs and non-tariff barriers to trade in goods; cooperate on investment, intellectual property rights, and competition policy; and establish and maintain an institutional framework for the implementation and administration of the AFCFTA.”

Finally, the agreement recognizes the regional economic communities as building blocks for the free trade area, encouraging RECs to continue trading among themselves according to their trade agreements. Article 19 of the AFCFTA agreement emphasizes that “state parties that are members of other regional economic communities, regional trading arrangements, and customs unions, which have attained among themselves higher levels of regional integration than under the Agreement, shall maintain such higher levels among themselves.”

Theoretically, the impact of a preferential trade arrangement is inconclusive. Scholars argue that lower trade barriers allow countries to expand trade within member states (a trade creation effect), which increases the welfare of these states. On the other hand, lowering trade barriers among member states may dampen trade with more efficient countries outside the agreement (a trade diversion effect), thus reducing member states’ welfare. Other macroeconomic effects include the terms of trade effect, the market expansion effect, and the competition effect.

In terms of trade effect, trade arrangements improve the bargaining powers of member states due to their increased influence over non-members because of the greater volume of trade between member states. The expansion effect is the economics of scale effect of a trade arrangement, including firms’ ability to choose the best locations for production and distribution as trade barriers are removed and markets expand. The competition enhancement effect under trade arrangement is the efficiency in production because companies with oligopolies in the region are made more competitive by market integration.

Trade theory asserts that while other effects would lead to positive welfare for member states in a trade arrangement, the trade diversion effect may have a negative impact, therefore the macroeconomic impact of trade arrangement might depend on whether trade diversion dominates international trade within member states.

The question —Do trade arrangements reduce poverty and inequality? — is a reoccurring theme in international trade literature. The general belief of policymakers is that international trade impacts the distribution of income via its impact on the level of income, the relative prices of goods, employment, earnings of workers, access to markets, technologies, and consumption patterns.

According to the trade theory, poor countries are usually relatively abundant in ‘unskilled’ workers. Within trade agreements, these countries become more specialized in ‘unskilled’ labor-intensive industries, increasing the relative demand for an ‘unskilled’ workforce. Consequently, trade arrangements would lead to an increase in the wages of ‘unskilled’ workers and lower the real wages of skilled workers in poor countries. While empirical evidence to support this theoretical assertion has been inconclusive, the trade literature claims the impact of trade on poverty and inequality is context-specific depending on the underlying trade mechanisms such as mobility of workers, industries, and geographical location.

The macroeconomic and distributional impacts of a preferential trade agreement are empirical matters. Most of the empirical literature on the discourse usually adopts a General-Equilibrium-Based analysis to examine the impacts. In what follows are results and discussions on the macroeconomic and distributional impacts of AFCFTA based on evidence obtained from an extensive review of recent empirical studies.

AFCFTA is expected to increase the efficiency of trade for member states in three ways. First, by reducing tariffs, AFCFTA will reduce the cost of goods and inputs for consumers and producers, respectively. Secondly, by easing administrative costs and technical trade barriers and requirements, the agreement will increase the efficiency of trade among member states. Finally, AFCFTA will increase the efficiency of trade in the region by reducing the compliance costs associated with technical trade requirements for consumer requirements and safety, by standardizing these requirements across member states.

This potential to increase the efficiency of trade in the region is further enhanced by reforms such as better border infrastructure which would reduce the transportation cost for imports and exports across member states. Furthermore, this efficiency will lead to an increase in the competitiveness of goods produced in the region leading to productivity gains, trade due to lower prices of exports and imports, and access to regional markets, thus fostering economic growth in the region.

1.1 Output

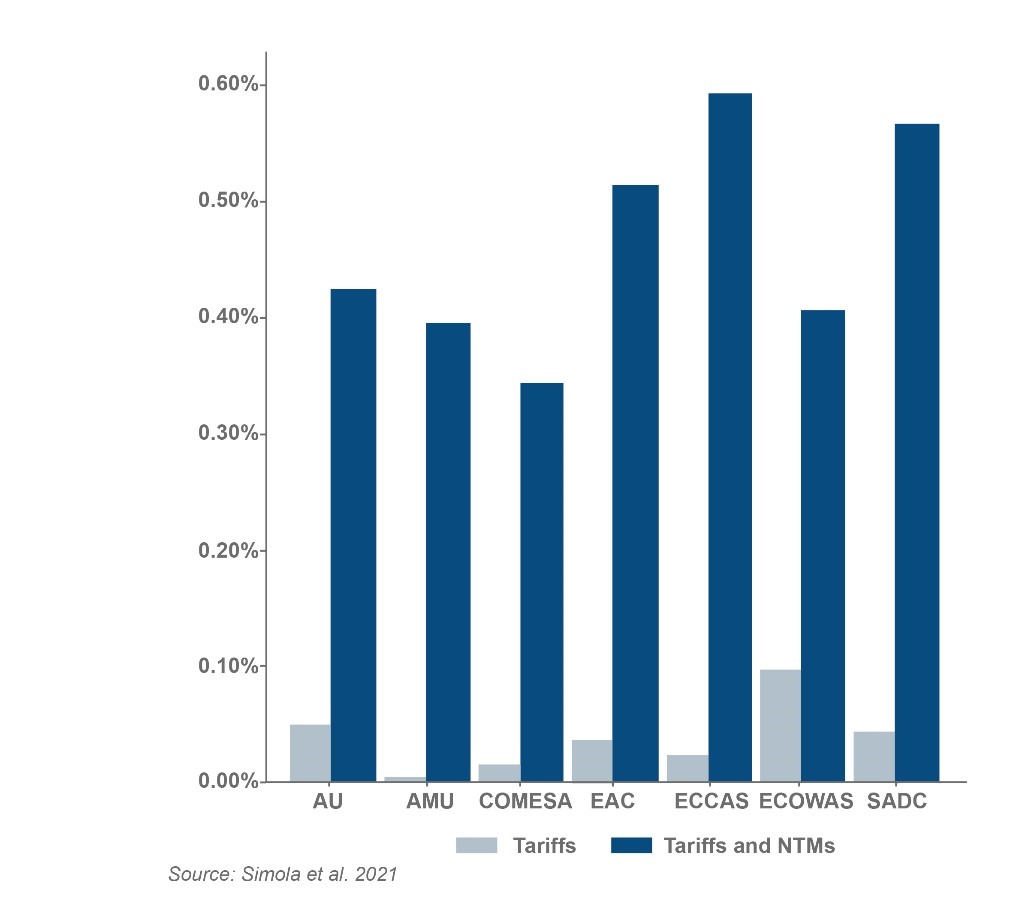

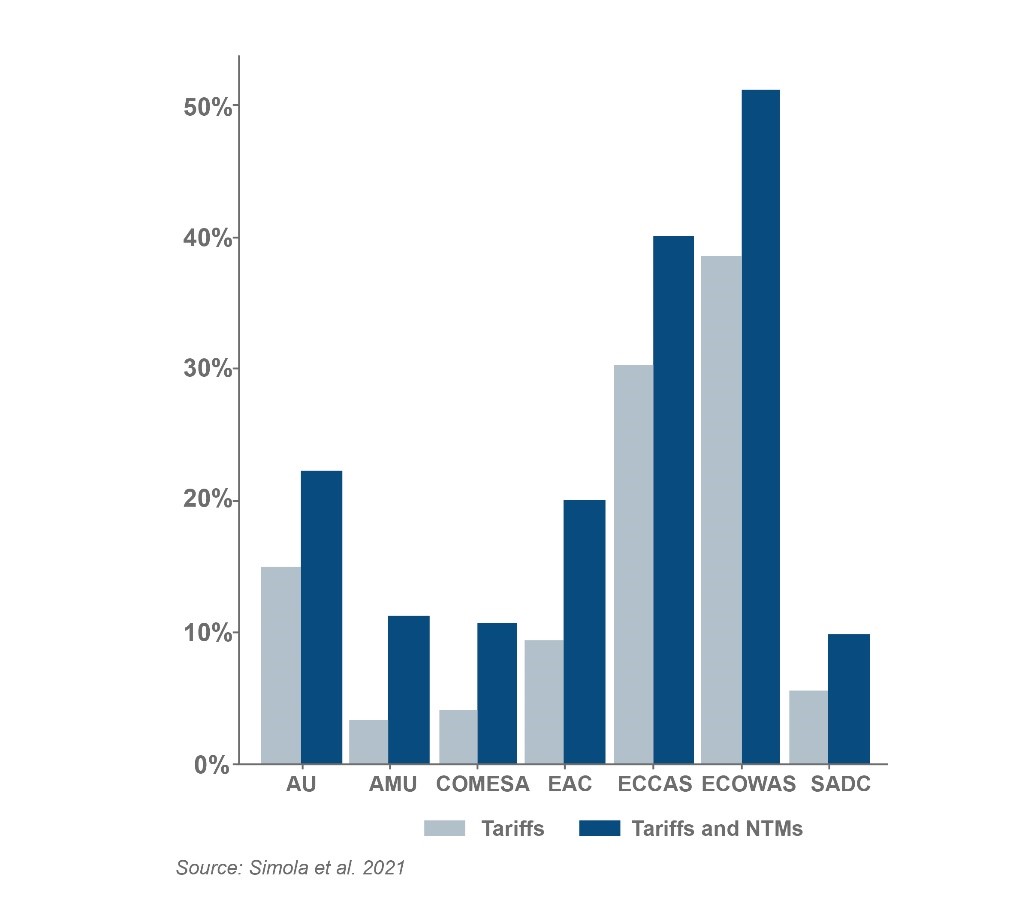

Empirical studies on the trade agreement’s impact on output find that output would increase under AFCFTA. Evidence from a recent study continues to support this belief. The study found that AFCFTA would increase GDP in 2035 by 0.42 percent for the whole region and between 0.33 and 0.59 percent across all regional economic communities with the Economic Community of Central African States having the largest increase in GDP. From their analysis, while there is little expected gain to GDP from the decrease in tariffs, a combination of a decrease in tariff and non-tariff barriers would lead to significant effects on GDP as shown in figure below.

Figure 3. Impact of AFCFTA on output

In monetary terms, the trade deal will increase regional output by $21 billion by 2035. Most of the gain is expected to come from the service and manufacturing sectors—$147 billion and $56 billion respectively. While agriculture is expected to decline by $8 billion in 2035; this suggests a shift towards services and manufacturing under AFCFTA, as the forecast shows likely expansion in these sectors across all regions in Africa.

1.2 Income

Several studies find that AFCFTA would increase income and welfare for most African countries. Many of the findings note small gains from lower import tariffs and larger gains from the elimination of non-tariff barriers. An important piece of evidence in the literature is that the welfare effect is uneven across countries. Small and more open economies would experience a large increase in welfare under AFCFTA compared to larger and less open economies. The main drivers of these gains are the manufacturing and agricultural sectors which account for over 60 percent and 16 percent of the welfare gains respectively.

Similarly, the World Bank’s report highlights the impact of AFCFTA on income in the region in quantitative terms. The forecast from the report shows that under AFCFTA, real income in the region would increase by 7 percent in 2035 ($45 billion), with noticeable gains (>10 percent) in Cote’ Ivoire, Zambia, Kenya, DR Congo, and Namibia.

1.3 Trade

The World Bank report also shows that the AFCFTA will facilitate trade in the region. Export volume for the region is forecasted to increase by 29 percent ($532 Billion) in 2035. 81 percent of this increase in exports will be intra-continental. This increase in export is expected to double or triple in Cameroon, Egypt, Ghana, Morocco, and Tunisia. Furthermore, export components —manufacturing, agriculture, and services— are all expected to increase with the highest gains in manufacturing, 62 percent ($823 billion) projected in 2035 for the region.

Similarly, intra-continental trade imports are expected to increase in 2035 from 18 percent to 25 percent under AFCFTA. Countries that would benefit the most in terms of imports include Cote ’Ivoire, DR Congo, Ghana, Tanzania, Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa.

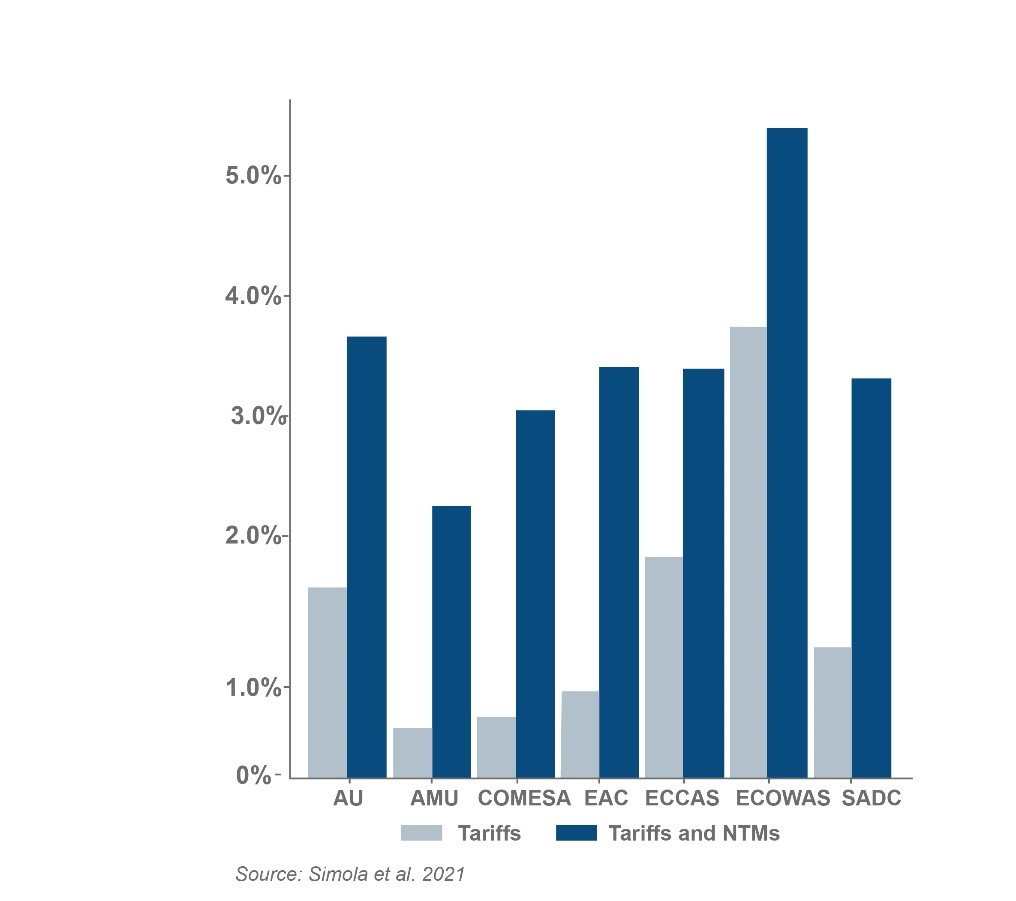

In terms of the impact on regional economic communities, forecasts expect imports to increase between 2.2 percent and 5.4 percent at the regional level, as shown in figure 4. Similarly, Figure 5 shows that Intra-African imports are expected to increase between 9.7 percent and 51 percent at the regional level. The increase is notably high in ECOWAS.

Figure 4. Impact of AFCFTA on imports

Figure 5. Impact of AFCFTA on Intra-African imports

Finally, several empirical studies show that AFCFTA would lead to an increase in intra-trade volume in Africa, a recent study find an 80 percent increase in intra-trade growth would occur under AFCFTA (a $60 billion increase in African exports), the total trade growth for the continent is expected to be about 8 percent.

1.4 Government Revenue

The AFCFTA will also impact the public finances of countries in the region. Most studies on the effect of AFCFTA on tax revenue show small losses in the short term due to tariff reductions. Tariff reductions would likely translate into lower tariff revenue in the short term for countries under the agreement. The world bank estimates a slight decline in tax revenue under AFCFTA in the short term—less than 1.5 percent—for most countries except DR Congo, Gambia, and Rep of Congo where tariff revenue would decline by 3.4, 2.7, and 2.1 percent respectively. These tax revenue losses according to one estimate will range from 0.03 percent to 0.22 percent of GDP ($1bill to $7bill) for the continent. However, over the long term, the World Bank estimates tariff revenue would increase by 3 percent for the region in 2035. Thus, while tariff revenue would decline in the short term, the increase in the volume of imports over time is projected to translate to higher tariff revenue over the long term—in 2035.

The impact on government revenue is nonetheless different in studies that account for tariff and non-tariff barrier reductions. Findings show tax revenue would increase when both tariff and non-tariff measures are considered in the analysis. This increase suggests the revenue losses from tariff reductions are likely to be compensated by higher consumption and income from the reductions in non-tariff barriers.

Empirical studies on the distributional impacts of trade policy usually focus on changes in the distribution of income between skilled and unskilled labor; the skill premium—the difference in the wages of skilled and unskilled workers. Many of these studies usually consider international trade as a key determinant of the increase in inequality in many economies. However, in some of these studies, the effect of international trade on income distribution tends to be context-specific, depending on the nature of trade policy, trade patterns, and mobility of capital and labor.

2.1 Income distribution and Poverty

Studies on the impact of AFCFTA on income distribution have been inconclusive. For instance, this study shows under AFCFTA countries that export agricultural goods experience a decrease in income inequality, while countries that export manufacturing goods experience increases in income inequality due to the higher skill premium.

Examining what AFCFTA might mean to extremely poor people living on the continent, the World Bank report forecasts that AFCFTA has the potential to lift 30 million people in the continent out of extreme poverty by 2035. The majority of this would occur in West Africa and Central Africa where the forecast expects 12 million and 9.3 million people will be lifted out of poverty, respectively. The report projects that the most significant decrease would occur in Guinea Bissau, Mali, Sierra Leone, and Togo at the country level.

2.2 Employment

Empirical studies on the impact of AFCFTA are usually based on general equilibrium models where unemployment is fixed, hence, most empirical studies do not capture the effect of AFCFTA on job creation. However, a recent study reveals interesting insights on the impact of AFCFTA on employment in the continent. The study finds the changes in employment under AFCFTA are likely to be small, ranging from -0.09 to 0.14 percent for the region.

This finding suggests job switching rather than job creation is likely to be more pronounced under AFCFTA. In the current scenario, agriculture, and wholesale/retail trade account for half of the employment in the continent. Under AFCFTA, the World Bank report estimates job switching will increase manufacturing and public service employment by 2.4 million and 4.6 million people, respectively.

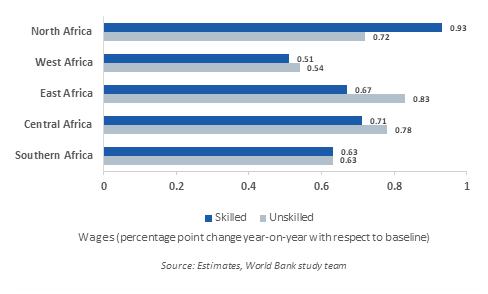

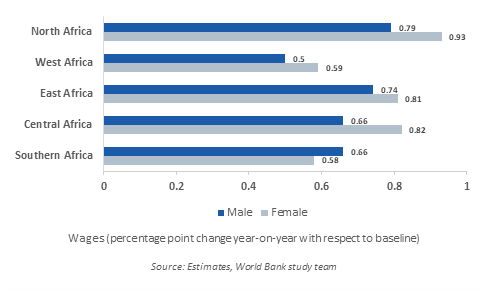

2.3 Wages and Gender

Figures 6 and 7 below from the world bank report provide significant insights into the impact of AFCFTA on wages and gender. From figure 6, wages for unskilled labor are expected to increase faster than wages for skilled labor in West Africa, East Africa, and Central Africa.

Figure 6. Impact of AFCFTA on wages by skill

Figure 7. Impact of AFCFTA on wages by gender

The reverse is however true for North Africa where skilled labor would grow by 0.21 percentage points more than unskilled labor. In terms of gender, figure 7 shows that AFCFTA will have an important impact on women’s employment on the continent. Female wages are projected to increase faster in all regions except Southern Africa. For instance, in Central Africa, female wages would increase faster than male wages by 0.16 percentage points. The World Bank believes this would be led by an increase in female employment in services and the agricultural sectors.

These projections by the world bank highlight the potential positive effect of AFCFTA in empowering the women workforce in Africa and the possibility of increasing opportunities for unskilled labor in Africa.

The empirical evidence discussed above suggests that AFCFTA will have a significant positive impact on the continent's macroeconomic environment and poverty reduction efforts. However, several challenges still need to be addressed to ensure the success of AFCFTA.

First, there is a need to ensure AFCFTA does not result in trade restrictions and diversion with other countries outside Africa. AFCFTA should not prevent African economies from participating in the global trade markets. Policymakers should use the opportunity created by AFCFTA to negotiate better trade terms with the rest of the world. By doing this, African economies’ share of global trade would increase, thus aggrandizing the positive impact of AFCFTA on the region’s economy.

Secondly, there is a need for coordination and cooperation between regional economic groups and AFCFTA. In the current arrangement (Article 19 of AFCFTA), regional economic groups are allowed to maintain their agreements where such agreements are broader than the AFCFTA. There is no clear guideline on the nature of the relationship between AFCFTA and regional economic groups.

Thirdly, there is a need to ensure the AFCFTA secretariat has the requisite mandate from member states to conduct monitoring, and oversight as well as provides the training and technical assistance to ensure the success of AFCFTA. Furthermore, out of the 54 countries in the agreement, only Ghana, South Africa, and Egypt have met the custom requirements on infrastructure for trading. This highlights the need for infrastructural financing and development in the region to ensure effective and efficient trade within member states under the agreement. Additionally, the regional governments need to strengthen their institutional capacity to monitor and control border activities and to address corruption, illicit trade, and smuggling across borders in the region which would likely increase under trade liberalization.

Finally, there is a need for effective international political economic management. This is necessary to ensure member states adhere to the successful implementation of the agreement and project phases of the AFCFTA as countries reform and respond to the structural and regulatory requirements necessitated by the agreement.

Abrego, M.L., de Zamaroczy, M.M., Gursoy, T., Nicholls, G.P., Perez-Saiz, H. and Rosas, J.N., 2020. The African Continental Free Trade Area: Potential Economic Impact and Challenges. International Monetary Fund.

African Union, 2018. Agreement Establishing the AFCFTA, 2018.

COMESA. Countries implementing the simplified Trade Regime Set to Rise. https://www.comesa.int/countries-implementing-the-simplified-trade-regime-set-to-rise/

C. Ntara, 2016. AFRICAN TRADING BLOCS AND ECONOMIC GROWTH: A CRITICAL REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE. Vol 4 International Journal of Developing and Emerging Economies

Department of Commerce, U.S., 2021. Rwanda – Country Commercial Guide https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/rwanda-trade-agreements

Free Trade Areas under COMESA and SADC: What the Literature Says about the Current Situation DPRU Policy Brief No. 01/P15 August 2001.

Kourtelis, C. (2021). The Agadir Agreement: The Capability Traps of Isomorphic Mimicry. World Trade Review, 20(3), 306-320. doi:10.1017/S1474745620000488

K. Schwab, World Economic Forum, 2018. Insight Report: The Global Competitiveness Report 2018. World Economic Forum

Maliszewska, M. and Ruta, M., 2020. The African continental free trade area: Economic and distributional effects. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

Pavcnik, N., 2017. The impact of trade on inequality in developing countries (No. w23878). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Simola, A., Boysen, O., Ferrari, E., Nechifor, V. and Boulanger, P., 2021. Potential effects of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) on African agri-food sectors and food security (No. JRC126054). Joint Research Centre (Seville site).

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), 2021. Economic Development in Africa Report 2021: Reaping the Potential Benefits of the African Continental Free Trade Area for Inclusive Growth

United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, 2019 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ar0ItKPq2cA

Urata, S., 2002. Globalization and the growth in free trade agreements. Asia Pacific Review, 9(1), pp.20-32.

World Bank, 2012. Let Africa Trade with Africa (44) Let Africa Trade With Africa - YouTube

This report was written by Hycent Ajah and Malcolm Durosaye