Reviewing Buhari’s Administration Cash Transfer Policy

June 21, 2023 | Hycent Ajah

INSIGHTS & OPINIONS

INSIGHTS & OPINIONS

Poverty remains one of the world’s most challenging sustainable development goals to tackle. This problem is particularly critical in Sub-Saharan Africa where the extreme poverty headcount is rising, prompting governments in the region to accentuate poverty reduction efforts.

Historically, governments across the world have adopted different strategies to address extreme poverty, such as welfare programmes, financial aid, and access to credit facilities for poor households. Often, the strategy adopted depends on the conceptualization of the cause of poverty—physiological or sociological. Physiological poverty explains poverty as the lack of basic needs such as income, food, clothing, and shelter. Strategies focused on this conceptualization would aim to increase the income of the poor. Sociological poverty is attributed to structural inequities such as laws that prevent the poor from accessing credit and agricultural lands. There is also the human capability concept which ascribes poverty to the lack of opportunities for the poor.

Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) policies follow a generalist approach to addressing the causes and the intensity of intergenerational poverty through the provision of financial support to poor and vulnerable households. Households eligible for these transfers typically need to satisfy a set of conditions, including mandatory school attendance and immunization of children, compulsory prenatal care, and compulsory participation in working activities. This programme successfully reduced inequalities and nipped intergenerational poverty in many Latin American countries.

The use of conditional cash transfers in Nigeria were first adopted by the Umaru Musa Yar’Adua Administration in 2007, under the “Care of The People” (COPE) Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) programme. The programme aimed to reduce the “vulnerability of the core poor in the society against existing socioeconomic risk and to alleviate intergenerational poverty” in Nigeria.

Under the COPE programme, participating households received a cash transfer of 1500 Naira per child up to a maximum of 5000 Naira and an investment payment of 84000 Naira or its equivalent in equipment to set up a petty business or trade. The eligibility criteria for beneficiaries of the COPE programme were households in communities with low human development indicators— girl child school enrolment rate and adult literacy rate, households with at least one child not more than Junior secondary school age, and households headed by vulnerable persons, women, the elderly, and persons with disabilities. The beneficiary selection process was overseen by the National Poverty Eradication Programme (NAPEP) and the Office of the Senior Special Assistant to the President on the MDGs who worked in concert with local government officials and community leaders—village heads, school heads, and religious heads. The main conditions for support were an 80 percent attendance record for school children in participating households and mandatory participation in government immunization programmes for children.

The COPE programme was developed with a core premise: income generated from petty business or trade would help lift households out of poverty. However, the COPE programme did have several shortcomings: household participation was limited to a year; community participation was limited to 10 households regardless of either the size of the community or the number of eligible households; and most significantly, the amount of the cash payment was often too small to structurally change a household’s poverty status.

Despite the shortcomings, during the COPE period, the poverty rate reduced from 47 percent in 2007 to 43.5 percent in 2010. Even with this reduction, the poverty rate was still high and remained around 40 percent in the years that followed under the Goodluck Jonathan Administration. Against this backdrop of poverty and hardship faced by many households in Nigeria, President Muhammadu Buhari established a CCT programme as part of the broad 2016 Social Intervention Scheme, part of a key campaign promise to reduce poverty through robust social intervention.

Overview of the Current Cash Transfer Policy

Expanding on the COPE programme, the administration launched a new CCT to lift vulnerable households out of poverty under a joint social intervention programme with the World Bank. The CCT programme was backed by a $1.3 billion funding commitment from the Nigerian government and a $500 million credit from the World Bank. In this current CCT, beneficiaries participate in the programme for three years in contrast to the COPE, which had a one-year limit. Additionally, while the COPE limited beneficiaries to 10 households per community, in the new CCT, data on all poor households in all communities across the country are entered into a national social register and eligible households are identified from the register.

To implement the programme, the Buhari administration first conducted a poverty mapping exercise to identify eligible beneficiaries for the national social register, i.e., the poorest and most vulnerable households. This was followed by a selection process wherein the National Cash Transfer Office (NCTO) identified eligible households for the national beneficiaries register. Selected beneficiaries are then enrolled in skill and business training to prepare for their potential exit from the programme. Currently, 12 million poor and vulnerable households (49.8 million persons) are registered on the Social Register.

Under the new CCT, beneficiaries receive a monthly payment of 5,000 Naira from the government. The payment is made directly to the main caregiver of the household, typically the mother. Furthermore, households receive an additional 10,000 Naira if they have pregnant women and school children, on the condition that the children regularly attend school and participate in government-approved immunization programme, and pregnant women attend periodic check-ups at primary health centers in or close to the community.

Impact on Households and the Economy

There have been several surveys of CCT beneficiaries. These exercises tend to rely on interviews of participants to ascertain the impact of the programme on welfare of these vulnerable households.

In a review of the programme two years after its launch, the National Cash Transfer Office asserts that the CCT helped prevent malnutrition and improve the livelihood of the poorest households in Nigeria. In several documented success stories, the NCTO presented testimonies from several beneficiaries on the impact of the CCT on their livelihood. Interviewed beneficiaries have attested to the improvement in their livelihood. These include improving their capacity to send their children to school; giving them business skills and support to grow their small businesses; improving their capacity to feed and clothe their kids; and empowering women in poor households to be self-sufficient.

One external review of the CCT finds that the programme helped smooth consumption patterns of participating households. Essentially, the extra cash allowed vulnerable households to find a balance between spending and saving, which in turn protected beneficiaries from financial hardship. What’s more, the communal design of the programme fostered solidarity among beneficiaries and strengthened participating families’ capacity to manage financial risk and avoid unnecessary disruption.

The Minister of Humanitarian Affairs emphasized the success of the CCT stating in a press brief, that since 2015, over 1 million households (7 million persons) have benefited.

However, looking at the overall data, the number of Nigerians in poverty has increased, from 40.1 percent in 2015 to 45 percent in 2023. This data suggests poor households are no better off now compared to 2015. In what follows, we discuss some issues and challenges for this.

Issues and Challenges

There are several issues with the current CCT programme. First, is the amount of the cash transfer; beneficiaries have acknowledged that the 5,000 Naira monthly payment is insufficient to make any significant change in their livelihoods, given the beneficiaries' short-term (3 years) participation, especially when we consider the inflation rate has averaged 13.97 percent over the past 5 years. Furthermore, in the last few years, the country has faced macroeconomic instability caused by the 2016 crash in oil prices and the Coronavirus pandemic. This economic instability has caused the Naira exchange rate to depreciate, reducing the purchasing power of households benefiting from the cash transfer scheme. A monthly payment of 5,000 would have difficulty significantly reducing poverty levels with these macroeconomic headwinds.

There is also a lack of data on how the poorest and most vulnerable households are identified for inclusion in the social register. The community targeting approach used merely relied on “subjective assessment,” which might not represent the household's actual poverty level. As documented, in some cases, the selection of beneficiaries was based on loyalty and personal relationships with the community leaders.

The NCTO has also failed to publish data on its performance and the impact of the programme on beneficiaries. The mere assertion of success based on the number of beneficiaries serve and testimony of a few beneficiaries are not enough; the NCTO must publish data to prove how the programme has helped improve the livelihoods of the poorest households. Publishing this data will create the necessary public awareness, improve programme accountability, and engender public support.

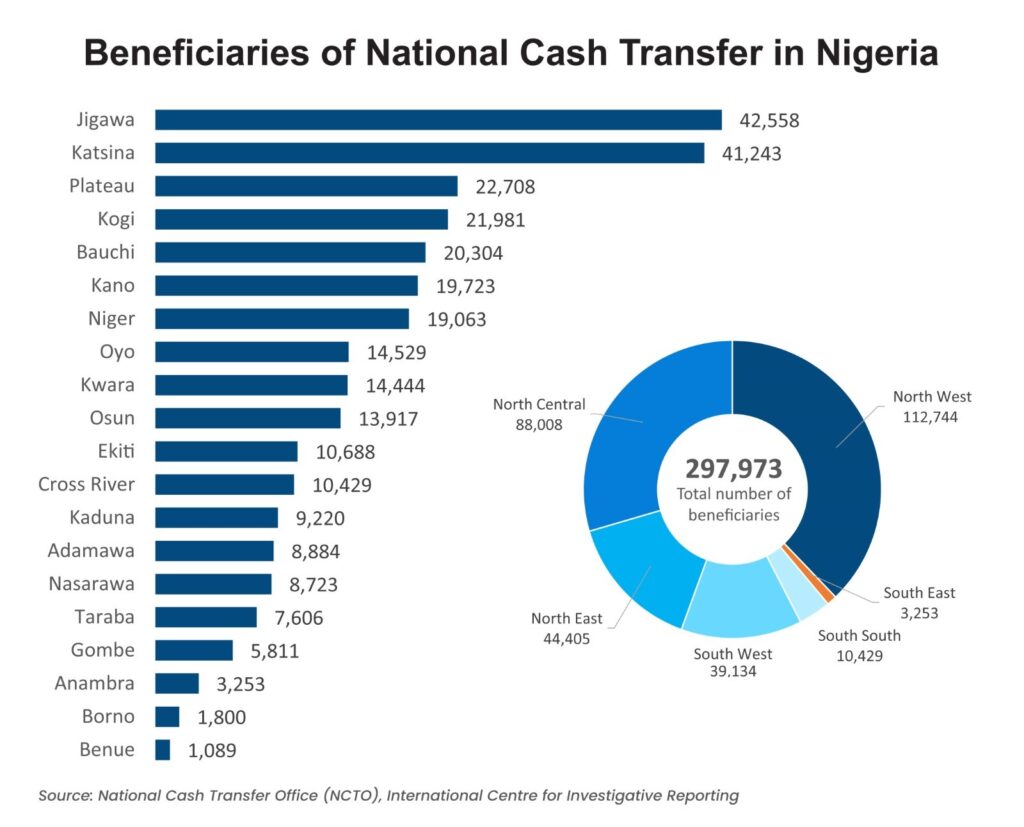

The geographical spread of beneficiaries has also raised public concerns. The figure below shows more beneficiaries in the Northern geo-political zones compared to other zones, with the South-East having the lowest number of beneficiaries. While this is plausible because a significant number (65 percent) of the extremely poor live in the northern region, there is still a suspicion of regional favoritism, especially when the total number of beneficiaries in Jigawa state is about 14 times more than the total beneficiaries in the whole of the South-East region (5 States). This uneven spread in the geographical coverage of beneficiaries raises questions about how beneficiaries were selected, the lack of specificity, and the need for the NCTO to publish an accurate account of its methodology for selecting beneficiaries.

Original Data Collated from: Ogunsemore John (The Herald)

Going Forward: NCTO Must Adopt Best Practices

Several best practices can be adopted to redesign CCT in Nigeria to improve the programme’s impact on poverty alleviation in Nigeria. Current and future administrations should consider adopting the periodic recertification of beneficiaries—the process of reassessing the socioeconomic status of beneficiaries and exiting households that are self-sufficient and have risen above a given poverty line. The approach is justified; since the goal of the CCT is to reduce poverty, then there should be no time-bound or maximum duration for a beneficiary to exit. Beneficiaries should participate in the programme until they no longer require income support. This approach has been widely used in Latin America, especially in Brazil and Colombia to improve the outcome of their cash transfer programmes. Since some beneficiaries of the CCT have admitted that 3-year maximum participation is insufficient to bring a significant change in their socioeconomic status, redesigning the programme in this manner could be a better approach to ensure beneficiaries exit when self-sufficient, in line with the programme’s primary objective.

The NCTO should also consider modifying its approach to selecting beneficiaries in a more specific and objective way. As earlier discussed, the current system relies on “subjective assessment” which could easily lead to a biased selection process or disparities in the geographical spread of beneficiaries. The NCTO should consider adopting a specific and broad objective requirement. Specificity would bring much-needed clarity to the selection process, while broadness would ensure all vulnerable families are included. For instance, in the USA, in the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) federal assistance programme, the eligibility requirements are as specific as possible with no subjective input on who is eligible as a beneficiary. Since income data might be difficult to ascertain in Nigeria due to the informal nature of most rural employment, other specific criteria can still be used such as the nature of employment, the number of children below secondary school age, and the main occupation of the caregiver and their years of work experience.

So far, the evidence suggests that cash transfer alone is insufficient to lift 88.2 million Nigerians out of absolute poverty. Federal administrations should consider a complementary approach, such as augmenting the CCT interventions with other key infrastructure improvements required to boost human capital and support the livelihood of people living in rural areas. This includes investing in the quality of schools in rural communities, improving the primary health services available in rural communities across all 36 states, improving the road and market network in rural areas, and increasing electricity provisions in rural communities. All these should be implemented alongside the CCT programme.

This article was written by Hycent Ajah