Electoral Violence: A Threat to Safe & Credible Elections in 2023

February 22, 2023

INSIGHTS & OPINIONS

INSIGHTS & OPINIONS

The historical significance of the 2023 Nigerian presidential elections cannot be understated, as it marks the longest period of uninterrupted democracy in the country. For the first time since the return to democratic governance in 1999, there is a frontrunner presidential candidate who is not running under either of the two major parties – All Progressive Congress (APC) and Peoples Democratic Party (PDP). This has changed the landscape of the electoral campaign this time around, providing Nigerians with more viable candidates to choose from instead of only having two options on the table.

The public expects the process to be more credible than previous elections given the new Electoral Act, which has been designed to address the disenfranchisement of citizens and ensure fairness, credibility, and transparency in Nigerian elections. However, there are still concerns about the state of insecurity in the country. For instance, recent security warnings from the United State Embassy and Consulate in Nigeria advising their citizens not to travel to 15 states in the country due to insecurity— crime, terrorism, civil unrest, and kidnapping—have exacerbated public fears. Despite this concern, the president and security agencies have reassured the public that the 2023 elections will be peaceful.

In what follows, we take a brief look at the historical issues of electoral violence in Nigeria, how these issues might pose a threat to the 2023 elections, and the measures that can be taken by the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) and security agencies to prevent violence in during the 2023 elections and in future elections.

Historical Cases of Electoral Violence

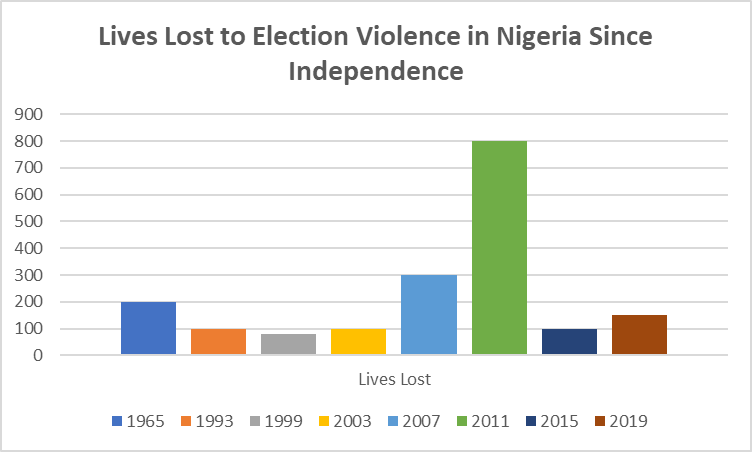

Since independence, Nigerian elections have often been plagued by intense disputes between political parties and candidates often leading to the use of violence to influence voters and protest in the wake of election results. In the country’s first post-independence election, Human Rights Watch estimates that over 200 people died, primarily in the Southwest, between 1964-1965. The unrest was caused by the failure of the Federal Electoral Commission to conduct a credible election.

The 1983 election was also alleged to have been tainted with cases of electoral malpractice and vote rigging, as well as the inability of the electoral tribunal to timely resolve electoral disputes. Consequently, violent protests, riots, and arson ensued, leading to the loss of numerous lives and extensive property damage.

The 1993 presidential election, which is regarded as one of the most credible elections in the nation's history, also had bouts of post-election violence. There were accusations of electoral malpractice, which led the military government of General Ibrahim Babangida to annul the election, leading to public uproar and a flurry of demonstrations. Beko Ransom-Kuti, the leader of the Campaign for Democracy (CD) at the time, estimated that security personnel killed over 100 nonviolent protesters. Protests and an extended political crisis continued for months.

The 1999 election that brought former President Olusegun Obasanjo to power, and transitioned the country from military to civilian rule, is the most peaceful election in the nation’s history. While there were seldom incidences of electoral violence due to the military’s intolerance for public disturbance, it has been reported, as shown in the chart below, that 80 lives were lost due to violent clashes between supporters of various political parties.

The 2003 elections saw renewed public disturbances. In the build-up to the elections, Human Rights Watch reported cases of voter intimidation and electoral malpractice by the incumbent party—the PDP. In several parts of the country, they reported cases of political assassination, intra-party violence, and the use of thugs to threaten and harass opponents. At least 100 people died due to incidents of violence triggered by the elections.

The 2007 election came with conflicts following an attempt by the incumbent President Olusegun Obasanjo to seek a third term as president. The Human Right Watch reported issues of electoral violence similar to the 2003 election—political assassination such as the murder of Funsho Williams, the PDP Lagos State Governorship aspirant, and clashes between political parties’ supporters. Human Rights Watch reported over 300 lives were lost in post-election violence, with pre-election violence alone taking over 70 lives.

The bloodiest incident of electoral violence in the nation's political history occurred in 2011. The post-election violence claimed at least 800 lives due to riots across the country over the results. The post-election period was characterized by religious and ethnic division. Muslim and Hausa/Fulani-dominated states targeted and killed Christians and other ethnic groups in the north, consequently, in several states in the south, there were reprisal attacks on Muslim and Hausa/Fulani communities. There were also reports of political assassinations, violent clashes between supporters, and bomb attacks in polling units.

According to the International Crisis Group, more than 100 people died during and after the general elections in 2015, mainly attributed to the pre-election attacks by the Boko Haram terrorist group. There were however still issues of clashes between supporters, intimidation of voters, disruption of polling units by gunmen, and the snatching of ballot boxes and electoral materials. The 2019 election also recorded cases of electoral violence–the European Union Election Observation Mission stated that violence associated with the election resulted in the deaths of 150 individuals.

This historical breakdown can be observed in the figure below.

Source: Kunle Adebajo/Human Right Watch

Security Threats to the 2023 Elections

In a recent press brief, INEC Chairman Mahmood Yakubu opined that the 2023 election could be cancelled if the security situations across the nation did not improve over the coming weeks. All geopolitical zones in the country are struggling to cope with various security challenges—militancy of religious extremists, separatist movements, banditry, kidnapping, and farmer-herder conflicts.

In the north, Islamist terrorist organizations like Boko Haram, Ansaru, and ISWAP have created enclaves in various locations throughout the states of Zamfara, Katsina, Kaduna, and Niger. They have constantly reaffirmed their opposition to democracy. The Ansaru, which has ties to Al-Qaeda, has already halted political campaigns in the Birni Gwari local government area of Kaduna state. There are also various gangs of bandits operating in the northwest, kidnapping and robbing citizens.

In the south-east, separatist groups, led by the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), which has subsequently split into at least three other factions, have consistently announced there will be no elections in the region. This is in addition to the compulsory sit-at-home being enforced on Mondays by the group in protest to the government’s arrest of the group leader—Nnamdi Kanu. Recent attacks against the Independent National Electoral Commission's (INEC) personnel and facilities have also been carried out by the group's armed wing.

Inter and intra party violence is another serious threat to the 2023 elections. According to National Security Adviser Babagana Monguno, 52 instances of political violence were reported in Nigeria in between 8 October and 9 November 2022, with the incidents spanning across 22 states. The Nigerian Elections Violence Tracker has recorded 130 violent incidents since the beginning of the year, along with at least 200 fatalities.

There is a very real possibility that these security issues will discourage eligible voters from going to the polls, causing voter turnout to dip even lower than the 34.75 percent recorded in 2019, posing a direct threat to the viability of Nigeria's democracy. It is also possible a low voter turnout would impact the outcome of the elections given the constitution’s requirement that the presidential candidate must win 25 percent of the votes in two-thirds of the states to be declared a winner. If no candidate reaches this threshold, a runoff will be held.

Preventing Violence: INEC & Security Agencies

Several measures can be taken by the INEC, security agencies and the government to prevent violence in the upcoming 2023 elections as well as in any future elections.

As discussed in our previous memo, to improve security in Nigerian elections, INEC should consider installing security cameras in all polling units to monitor the security situations across the entire country on election day. Additionally, INEC should invest in professional training of its officers and undertake background checks on their criminal history and party affiliations. Partiality and collaboration of INEC officers with political parties to rig elections results has in the past instigated other political parties who feel cheated to adopt violence as a means of expressing their anger and frustrations. INEC must put in place policies and controls to ensure its independence, impartiality, and transparency in elections.

INEC should cooperate with security agencies to set up a social media platform where citizens can track, monitor, and report activities in their polling units. This will enable security agencies to obtain information and act promptly to quell any incident of electoral violence. Also, as discussed in our previous memo, the INEC should work with the judiciary to streamline the timeline for the resolution of electoral disputes and to ensure consistency in electoral laws and electoral rulings. The Judiciary and the law enforcement agency must also be proactive in arresting and prosecuting individuals and political parties engaged in or sponsoring electoral violence. This could also include placing a lifetime ban on political parties and individuals found guilty of rigging election results and perpetrating electoral violence.

The INEC must encourage political parties to be inclusive of all religions and ethnic groups. Cases of electoral violence, particularly in 2011, 1983, and 1965 could be attributed to ethnic and religious division among Nigerians. Political parties should be mandated to foster a culture of inclusion in their party activities, including through the following guidelines:

While not completely exhaustive, these requirements could prevent religious and ethnic divisions from festering and decrease sentiment that some political parties only belong to certain ethnic groups or religions. In addition, INEC should collaborate with ethnic and religious leaders to proactively use their influence to encourage followers in a peaceful electioneering process.

The INEC must also set guidelines for political campaigns. Political parties should be mandated to only engage in issue-based campaigns. All forms of bigotry against an opponent's region, religion or ethnicity should be discouraged.

There is also the need for the INEC to invest in public education on electoral laws and guidelines. Inadequate public knowledge of electoral laws and guidelines was one of the causes of electoral violence in 1993 and 2011 elections. INEC must make sure citizens understand electoral laws and guidelines and the conditions a candidate must satisfy to be declared the winner. This way, ignorant political party supporters who feel cheated do not resort to violence to express their grievances over an election that they fairly lost. (See our database for access to electoral laws and guidelines in Nigeria and other countries in Africa)

As noted in the literature, one cause of electoral violence is the desire for political power by any means necessary due to the affluent salaries and allowances of political office holders. Politics is now viewed as a get rich quick business, where winning an election turns one into a millionaire. There is a need to change this notion, potentially by reducing the salaries and allowance of political office holders to modest levels that would dissuade those solely in the job for the high pay. This could help curb the desire for political power by any means necessary and prevent electoral violence.

INEC could also put a limit on the amount political parties charge candidates for party nomination forms for political offices. In the nomination for presidential candidates for the 2023 elections, the two major political parties, APC and PDP charged aspirants 100 and 40 million Naira respectively for their nomination form. These exorbitant charges make politicians approach elections with a mindset of “winning-by-any-means-necessary” in order to recoup whatever they spend in the electioneering process. There is also the need to curb vote buying—paying voters to vote for you. With so much money spent during the electioneering process, politicians usually resort to using violence to protest if they do not win. However, if the cost to entry was lower, there may be less at stake and thus some politicians would not seek retribution in the event of an electoral loss.

Finally, as discussed in our previous article, the media must play its part by providing unbiased coverage of the elections, treating each candidate, regardless of their ethnic group or religion, with respect. The media must be unbiased and should not be susceptible to misinformation or propaganda. The National Broadcasting Commission could put in place sanctions for any media reporting unconfirmed electoral results. In the past, unconfirmed reports of election results caused public confusion, with political parties claiming victory before the announcement of the official result. This heightened tensions and contributed to violence when the official results, which contradicted earlier reports, were made public.

As the country votes this weekend in perhaps the most competitive presidential election in its history, given the country’s fraught experiences of pre/post-election violence. There is a need for the INEC and security agencies to adopt some of the measures highlighted above to ensure a safe and smooth election.

This article was written by Hycent Ajah and Tamara Etifa