Nigeria’s 2023 Elections: policy options to address voter apathy

September 22, 2022

INSIGHTS & OPINIONS

INSIGHTS & OPINIONS

Nigeria’s next general elections could arguably be the most pivotal election since the country’s return to democratic governance in 1999. It could easily become a make-or-break moment for Nigerian democracy considering growing tribal and religious sentiment towards electoral processes across the country. Judging from recent states’ election results, reforms provided by the Electoral Act 2022 have ushered progress into the electoral process. These reforms and evident governance problems have sparked mobilization campaigns; numerous Nigerians have now registered and collected their Permanent Voter Cards (PVC) ahead of the coming elections. However, further actions need to be taken by stakeholders to improve and ensure active citizens participation in the electoral processes.

Voter apathy is a major challenge to Nigerian democracy. There is a worrying trend of public disinterest in or indifference towards the electoral and democratic processes. This lack of interest is a major factor influencing lower voter turnout in elections where voting is optional. Electoral participation is a critical aspect of democracy since it allows citizens to get involved in the political process. Analysis of political science literature shows that electoral participation is a key indicator of democratic performance. The impact of citizen nonparticipation can be broadly categorized by three distinct phenomena: the accountability effect, the representative effect, and the legitimacy effect.

The accountability effect refers to the inability of citizens to discipline poor-performing elected officials and political parties by not re-electing them into public office as well as voting for a different party in subsequent elections.

The representative effect lays out a simple question: if most eligible voters fail to participate in the process, is the elected government a true representative of the people? This is especially critical since one of the basic tenets of democracy is a representative government that reflects the choice of most of the citizens.

Finally, the legitimacy effect means the nonparticipation of citizens in the elections weakens the legitimacy of a democratic government. It is argued that the absence of most citizens in the voting process questions the legitimacy of the election to select competent individuals for public office.

Historical data indicate low citizen participation in the voting process since Nigeria’s return to democratic governance in 1999. The data reveal that while Nigerians consistently participate in voter registration, they are less enthusiastic about casting their votes on election day. In 2019, for example, the country recorded the lowest voter turnout in Africa, despite the increase in registered voters. Voter apathy is even more evident in the National Assembly representative elections; more Nigerians participate in presidential and gubernatorial elections than in the National Assembly and the local government elections. The implication is clear: Nigerian voters believe executive positions are more important than legislative seats.

Voter apathy in Nigeria (historical data)

Data from the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) on past elections show that only a small percentage of Nigeria’s voting population votes on election day. Unfortunately, this voting behaviour is a challenge to democracy and effective, forward-thinking governance as election results might not accurately reflect the public’s choice. Take the last general election as an example, where only 28.6 million out of 82.3 million registered voters cast their ballots on election day in 2019.

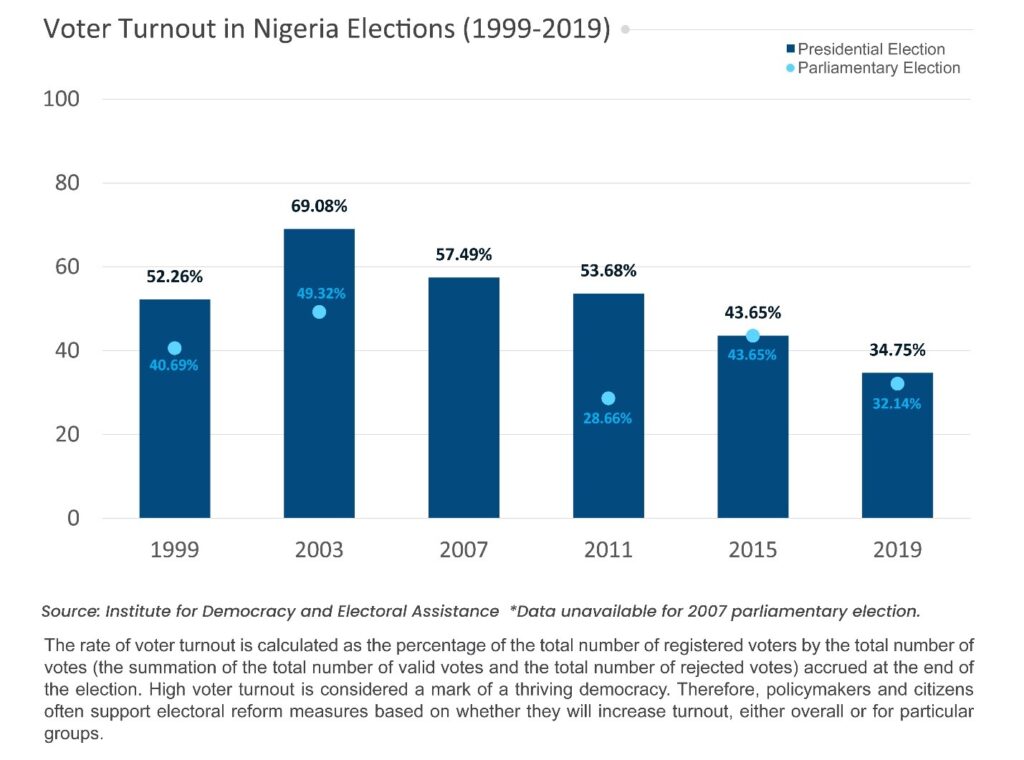

Voter turnout is the percentage of eligible voters who show up to cast their votes in an election. Statistics from INEC capture the disheartening trend in voter turnout in Nigeria’s elections: 52.3% in 1999; 69% in 2003; 57.5% in 2007; 53.7% in 2011; 43.7% in 2015 and 34.8% in 2019. This can be observed in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1

Breaking down the data by election type provides more insight to the discourse:

Presidential Elections

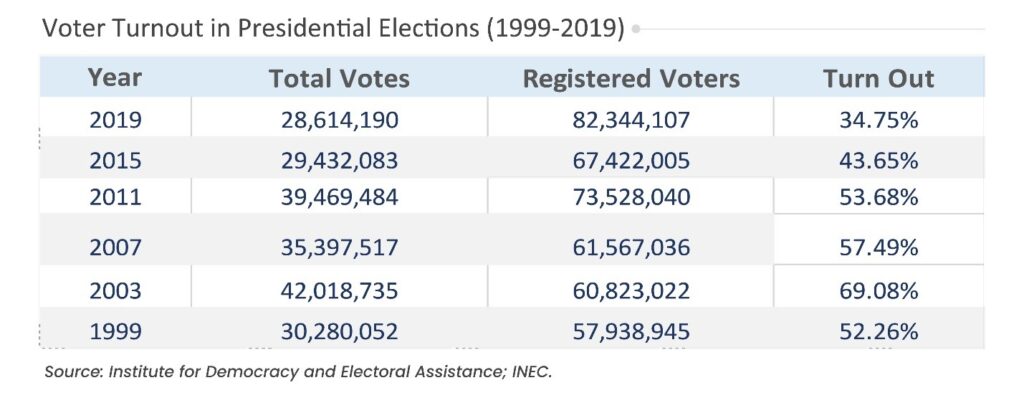

Nigeria’s return to representative democracy in 1999 yielded a 52.2 percent voter turnout, with 30.2 million out the 57.9 million registered citizens voting. Both the number of registered voters and number of ballots cast increased in the following election in 2003, with 42 million out of 60.8 million registered Nigerians voting (69 percent voter turnout). This remains the highest rate of participation since the end of military rule in 1999.

In 2007, despite an increase in the number of registered voters to 61,567,036, total votes cast significantly dropped to 35,397,517 (57.5 percent voter turnout). Registered voters and total votes further increased to 73,528,040 and 39,469,484 respectively in 2011 and then dropped to 67,422,005 and 29,432,083 in 2015.

2019 was a disturbing and surprising election year for Nigeria. The number of registered voters shot up by almost 15 million to 82.3 million. However, the country recorded the lowest turnout rate of the fourth republic with only 28.6 million people voting (34.75 percent voter turnout).

Parliamentary Elections

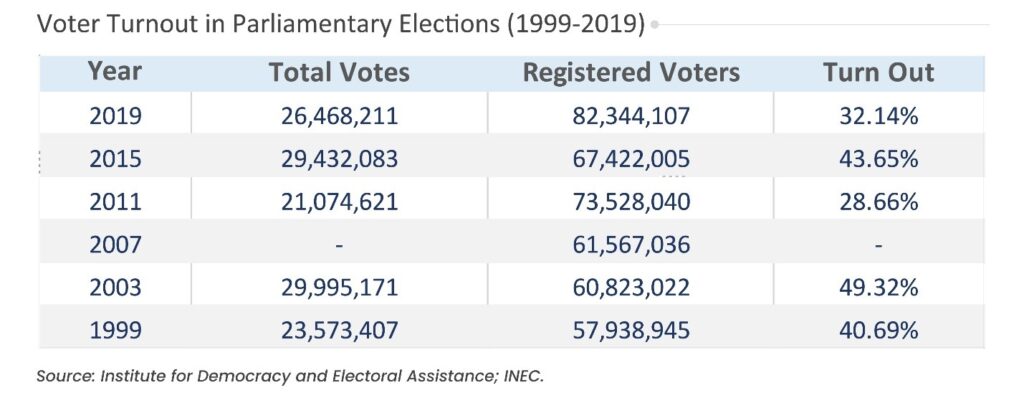

Voter apathy is more widespread in Nigeria’s parliamentary elections — turnout in parliamentary elections is typically much lower than in the presidential elections. In 1999, only 40 percent of registered voters cast votes to elect their representatives. Fewer than 50 percent of registered voters cast their votes in 2003 compared with 69 percent in the presidential election. The parliamentary turnout rate dropped drastically to 28.7 percent in 2011, then rebounded to 43.7 percent in 2015, before dropping to 32.1 percent in 2019.

Voter participation in the presidential and parliamentary elections have become more identical since the 2015 general elections because INEC started conducting both polls same day. Various innovations to improve participation were also introduced in 2015, including the use of card readers in the voter accreditation process.

Gubernatorial Elections

Turnout in gubernatorial elections varies across Nigerian states. Data from the 2019 gubernatorial elections show that many states recorded low voter turnout in their elections. From turnout rates above 50 percent only in Borno, Jigawa, Katsina, and Taraba to a worrying low of 18 percent in Lagos state, the country’s financial capital.

Causes of Voter Apathy in Nigeria

Voter apathy in Nigeria can be attributed to several factors. One major factor is inadequate voter education. Many eligible voters lack a complete understanding of the voting process, including political parties’ ideologies and candidate selection processes, the requirements to participate in the voting process, and the procedures for voter registration. Many voters are unaware of the INEC voter registration deadline and do not know where to pick up their voter card. The lack of voter education is particularly challenging in more rural communities where there is limited media access and low literacy levels.

Another cause of citizen disinterest are the inefficiencies of the voter registration and the voting process. The voter registration process is often time-consuming, inconsistent, and riddled with mistakes. For example, there are complaints of long queues at registration centers, absence of staff at the registration centers, faulty machines, missing voter cards, and poorly trained staff. These inefficiencies which are present in all steps of the process create an unnecessary burden on voters, discouraging them from actively participating. One common issue is when voters are assigned polling units far from their residence forcing them to travel unfair distances. While it is difficult for some domestically based Nigerians to get to their polling units, there are no voting options at all for the quite significant number of Nigerians in the diaspora.

In addition to the inefficiencies of the process, electoral fraud and rigging are another blot on INEC’s record. First hand reports of brazen fraud and rigging is an all-too-common experience. This ranges from discrepancies in INEC-announced and polling unit-announced results to open bribing of INEC officials. Other examples of corruption in the process include vote buying, ‘donation’ of food and other items to citizens in polling units. Even outside the direct electoral process, judicial rulings on election cases many times carry an air of fraudulence. There is also a general disbelief in INEC’s independence and an expectation that the electoral commission would manipulate results in favor of the incumbents or more affluent politicians. All told, these experiences and expectations sour voters’ belief in the electoral process, making voters believe the electoral process is a waste of time.

Further to this, many eligible voters are wary of electoral violence. This includes intimidation of voters supporting opposing candidates; use of hired thugs to intimidate voters and disrupt voting at polling units; snatching of ballot boxes and voting materials by hired thugs of political parties; clashes between supporters of rival political parties like the post-election violence in the aftermath of the 2007 general elections; and ethnic and religious-driven campaigns that exacerbate existing tensions and conflicts.

Bad governance and uninspiring politicians also encourage voter apathy. The country’s political class is disappointingly composed of several criminals. Many of them have been indicted for money laundering and misappropriation of public funds. Beyond criminality, another uniting characteristic is unabashed personal ambition with little regard for professed ideology. There is a culture of politicians defecting from one political party to another for their ambitions. For instance, prior to the 2015 general elections, affluent politicians moved from the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) to the All-Progressive Congress (APC). Most voters consider the defection of politicians as a recycling of underperforming politicians under different platforms. Furthermore, the failure of political parties and politicians to fulfill their campaign promises makes eligible voters believe elections have no positive impact on their life. Many voters say politicians are unaccountable and their actions after elections do not represent the citizens’ interest, with favoritism shown to allied ethnic groups, regions, family, and friends.

What’s more, many eligible voters are aware of the corrupt party primary process and the lack of internal democracy. The bribing of political party delegates in the recently concluded party primaries has brought to light a worrying phenomenon: “the dollarization of delegates.” This refers to how aspirants bribed delegates with dollars to secure their votes. There is also a tradition of governors and presidents getting automatic party nominations for second-term elections regardless of their first-term performance. Additionally, there are incidents of imposition of party candidates by party leaders and patronage in the selection of party candidates. These issues have in the past led to the emergence of candidates without the capacity to deliver party campaign promises.

On top of these issues are the challenges of insecurity and poor transport infrastructure. Lack of adequate transport infrastructure, high cost of air travel, and the security challenges of traveling —kidnapping, bandit attacks, and terrorist attacks — mean many eligible voters are unable to travel for voter registration and to participate in the voting process.

Policy Options

There are several policy options available for political stakeholders looking to address the problem of voter apathy in Nigeria. The Independent National Electoral Commission should consider new ways of voting such as mail voting and the use of Electronic Voting Machines (EVM) for voter identification, voting, and tallying. Evidence from Brazil shows EVM could be used to eliminate electoral fraud and rigging. The Electoral Commission could also install security cameras in all polling units to monitor security situations and curb vote buying. Furthermore, the commission should specify clear guidelines for the timely and consistent resolution of electoral disputes (For example, not more than 30 days after the election). INEC must also ensure political parties and candidates found contravening the Electoral Act are barred from participating in future elections. This will incentivize political parties and candidates to act lawfully throughout the electioneering process.

Security agencies, including the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission and the Police need to cooperate with the INEC to ensure their presence in all voters’ registration centers and polling units across the country. This would help curb violence and vote buying in registration centers and polling units. Security agencies must collaborate with the Judiciary to investigate cases involving electoral crimes as stipulated in the Electoral Act. Furthermore, security agencies must discharge their duties following the rule of law and maintain impartiality to candidates and political parties.

Civil society organizations who serve as electoral observers and the media must be unbiased to candidates and political parties. This means robust media coverage of elections, campaigns, and activities of political parties and curbing the spread of fake news and libelous propaganda. The media should take care to report only confirmed results and avoid reporting results in units where voting is still in progress.

Policymakers should consider making voting compulsory; all registered voters should be mandated to vote or otherwise pay a small fine. A similar policy in Australia has ensured high voter turnout (about 95 percent in some elections).

The Electoral Act must stipulate clear guidelines to prevent the chief executive from using state apparatus in favor of their party or preferred candidates. The president should also be prevented from interfering in the activities of the INEC, security agencies, the Judiciary and in the selection of party delegates.

Political parties should also ensure transparency and fairness in intra-party activities. This will involve the development of guidelines to prevent the imposition of candidates and intra-party vote buying. Parties need to also formulate clear ideologies that are easily identifiable by voters. This would allow voters to develop affinity for various parties and potentially limit cross-carpeting of politicians from one party to another.

Finally, the judicial branch should be non-partisan and fair to candidates and political parties. The judiciary should not subscribe to the influence of executive power. Furthermore, the judiciary should streamline and outline the judicial procedure for quick resolution of electoral disputes and consistency in the electoral ruling (for example, not more than 30 days after the election); in the past, ruling on electoral disputes by state high courts has been overturned by the Supreme court, leaving voters discontent.

It is unlikely that any of these policy options will be incorporated ahead of the upcoming general elections. However, if Nigeria intends to solidify its democratic principles, it is hugely important for all political stakeholders to adopt some of the above listed policy options to address the issue of voter apathy and increase voter turnout.

This article was written by Hycent Ajah